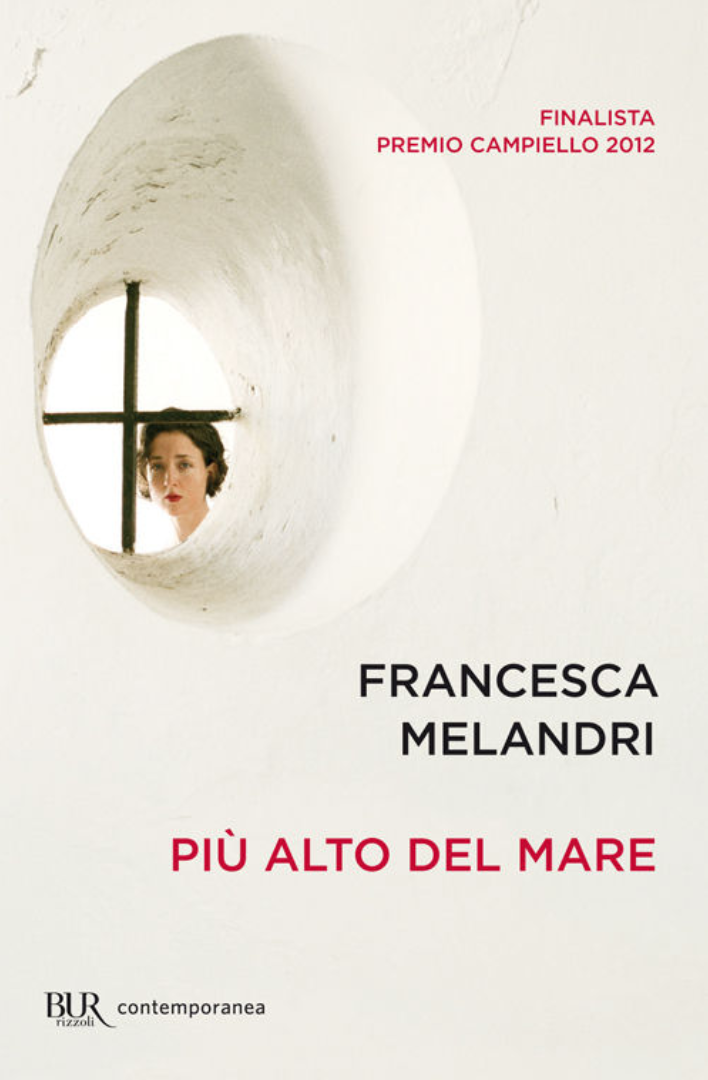

Higher Than the Sea by Francesca Melandri

- Lucy Rand

- Apr 23, 2020

- 7 min read

Più alto del mare

Rizzoli

February 2012

240 pages

“Because, if you want to keep someone truly separate from the rest of the world, there is no wall higher than the sea.”

Francesca Melandri, author behind March’s ‘letter from the future’ (The Guardian), from Italy to the rest of Europe, is a highly acclaimed novelist and screenwriter from Rome. Melandri’s books explore some of Italy’s darkest and unexplored historical events through captivating portraits of human lives. In her first novel, Eva dorme (translated into English by Katherine Gregor as Eva Sleeps) the civil unrest of the Italy-Austria border region is woven through the lives of two women across five decades. Più alto del mare, finalist of the 2012 Campiello Prize, illustrates the effects of the decade of violence known as the ‘Years of Lead’ on the innocent family members of two perpetrators. And her most recent novel, Sangue Giusto (2017) investigates the social and psychological impact of Fascist Italy’s East-African empire.

Higher than the Sea opens with the transfer of some of Italy’s most dangerous criminals to a maximum security prison in the dead of night. The prison is on Asinara, a small island off the north-west coast of Sardinia, otherwise inhabited by wild horses, albino donkeys, goats and the extraordinary scent of ‘of salt, of figs, of curry plant.’ It is the end of the 1970s and Italy, assailed by bombs, kidnappings and murders, is under a regime of zero tolerance. The prison on Asinara is the symbol of this tough regime.

'The spicy air, no, that they didn’t expect.

That they would come at night, they had always imagined, and, indeed, they pulled them out of prisons all over Italy when the sky was black as a rotten tooth. They came in chinooks, ta-ta ta-ta ta-ta as if they were coming in direct from Vietnam, not Praia a Mare or Viterbo.

…

The fear of dying was there, and yet all of them, as they got into the helicopter, raised their eyes to the sky. The moon was new and it was dark. They had taken care of that too when planning the operation, so there would be no shimmer on the sea to reveal the shape of the coastline from above. But not even the secret agents of imperialism and capital could extinguish the stars that were there, pulsating and sharp. There were those among them who had not seen the stars for months, others for years. Who knew when and if they would ever see them again.'

Paolo and Luisa, two strangers, are on the ferry from the main island to Asinara for the prison’s visiting hours. Luisa, a peasant and mother of five from the mountains of north east Italy is dutifully visiting the husband she has been out of love with for a long time. He is in prison for a series of murders. Luisa is oblivious to his involvement in the national wave of terrorism and is instead focused on the sea, which she has never seen before. For Paolo, an ex philosophy teacher and widower, on the other hand, the smell of the island prompts memories of summers by the sea with his young son. This son is now in prison for murder as a member of the far-left terrorist group, the ‘Red Brigades’. Paolo is tormented by guilt that he brought his son up to fight so savagely for his beliefs.

'The island was not far out at sea but it might as well have been. Between there and the mainland, which wasn’t actually the mainland but one of the larger islands, there was only the Strait, which looked easy enough to swim across. The winds swept away any mist, smoke or impurities from the air, even the blackish clouds from the petrochemical plant. This made the Island look really near, almost close enough to touch – but it was an illusion. It was the strong winds of the Mediterranean, which from there lay wide open all the way to Gibraltar, that gave such clarity to its outline. But the Strait was riddled with currents that would inhibit the crossing of even the most vigorous swimmers.

…

On the deck there was just the African woman, Paolo and a blond lady he felt he’d seen before. She could have been either thirty or fifty. She was one of those women who you imagine at twelve years old already able to look after their younger siblings, make soup, iron the laundry, and who at twenty already convey the calm efficiency of middle age. Not that she was heavy or plump, on the contrary, her body had the tone and muscle of one that is used a lot. Maybe she was an athlete when she was young? The dress she wore seemed like it was her best, though creased from a journey that had probably started long before they cut through this last stretch of sea.'

On this particular day, due to the approaching mistral, a cold north-westerly wind common in the Mediterranean winter, Paolo and Luisa are the only two visitors. The storm forces the pair to spend the night on the island, and the pain that cripples their lives becomes intertwined in an almost unspoken mutual understanding that is at once intangible and deeply penetrating. Luisa and Paolo spend the evening in the company of the guard Pierfrancesco Nitti, who becomes the novel’s third protagonist, and his wife. Their once blissful marriage has been poisoned by the violence, cruelty and inability to speak engendered by daily life at the prison, and the lack of understanding between them is salvaged by the unexpected visitors.

Melandri’s prose is generous and lyrical, yet there is not a word that needs to be cut. Her descriptions of the island are intensely lush and refreshing, in stark contrast with the brutality and coldness of the prison.

The rocky headland proceeded inwards in a series of increasingly rugged precipices. In the distance, the Island culminated in the isolated and almost alpine peak of a mountain. At the other end of the bay, the ruins of a circular tower emerged out of a smooth, green promontory. This part looked like a piece of Ireland that had been dropped into the middle of the Mediterranean. The dirt track in front of them followed the narrow strip of earth that separated a pond from the sea. With every surge, the waves threatened to swallow up the road and unite the two bodies of water. Not far from the van, on the wide plane in front of the pond, stood a group of wild horses. They were immobile, their eyes half-closed, with limitless patience. They were all facing in the same direction: head downwind, rump to the mistral.

These descriptions of the island, seen through Luisa’s eyes reveal an unaffected appreciation of beauty. She is a character I’ve never read before and I found her captivating. She embodies a childlike curiosity that is unafraid to ask questions, though the trauma and hardship of her life is revealed, perhaps, in her obsessive counting:

They weren’t little children anymore like at the beginning, when Anna, the eldest, was only eleven, Luca two and the other three in between. Now the youngest in the house was the same age as the oldest back then, twenty. Twenty! Two years older than Luisa when she got married…

There she goes, calculating again. Counting, always counting. It was stronger than her. She counted all the time, especially before going to sleep. She counted the litres of milk delivered to the Dairy; the weeks left until one of the cows gave birth; the age of each of her children the night the carabinieri took their father away. She counted the numbers on the meter to see where she could save, even if the children knew they couldn’t switch the light on until it was so dark they were bumping into the walls. She counted the washing machine payments and recounted the money she would make. Like that time a butcher was buying a calf from her and she realised straight away that he had given her fewer notes than due. And she also knew why: people think a woman without a husband is easier to dupe. But she had counted, recounted, then coolly and calmly asked him for what was missing, else she wouldn’t load the calf onto his truck. The man had pretended it was a mistake, that he’d messed up the calculation. Of course. He wouldn’t have done that if he’d known that Luisa counted even the wooden rods on the benches in the church porch (eight) and the steps between the door of the house and the barn (twenty six).

Paolo carries his guilt in his pocket. He keeps in his wallet a newspaper cutting depicting the daughter of one of his son’s victims at her father’s funeral. In the middle of the night, both unable to sleep, Luisa asks him about it:

“But, why do you keep it in your pocket?”

He lowered his eyes onto the piece of paper and kept them there. As if in those letters, in that photo, in that little girl’s hat, he’d find the answer to her question. He let out one of his painful sighs, almost a whimper – and this time it was clear that he had heard it too. He gave her a look that was so unarmed, pained, defeated that for a moment Luisa stopped breathing.

“Because it’s the last thing left of my son.”

Luisa forgot to exhale. Her shoulders were still raised and for a long moment she held her breath.

When she breathed out again, her eyes were filled with tears. She lifted her arm. Reached out her hand. Moved it towards Paolo’s face and brushed it. Slowly, with the tips of her fingers.

Paolo closed his eyes. He tilted his head slightly to lean into her fingers. He stayed still, his eyelids closed, his cheek wrapped in Luisa’s hand. Then he grabbed it and pushed it against his cheekbone and stayed like that for a long time, without opening his eyes, which were like a sealed box full of pain, holding onto her palm tight to console his face. Finally, suddenly, with his eyes still closed, he put his arms around her and pulled her in.

Reviews from Italy

'The true value of this novel, as Calvino would say, is in its lightness, its floating like a soap bubble between past and present, a rippling suspension between memory and grief, guilt and the courageous acceptance of destiny … [Francesca Melandri’s] quiet, fluid style and tendency towards descriptions that often verge on the lyrical, attenuate and render more tolerable the tensions buried between the lines.'

Silvia Mazzucchelli, Doppiozero

'A linear novel of remarkable intensity, that moves us through moments burning with modesty. This story won’t leave anybody cold.'

Stefano Trabucchi, Solo Libri

'A narrative that is far from banal, set in a dark period of [Italian] history, treated with lightness of touch and great sensitivity. There is a sense of time fading and soothing the pain.'

Sandro Russo, Ponza Racconta

English Rights Available

Rights queries: The Italian Literary Agency

Contact: Claire Sabatie Garat, claire.sabatiegarat@italianliterary.com

Rights already sold for translations into French, German, Dutch, Croatian and Ukrainian.

[Translations all my own]

Comments